♰ the tenets of medieval-girl autumn ♰

devotion, teeth, soil & mud, chainmail armour, furs, Julian of Norwich, pilgrim badges, compline & evensong, amulets, holy tattoos, folk sex-rituals (baking bread), frankincense, the pearl-maiden, piety but in a bloody, erotic kind of way (ecstatic revelation), weaponry, feasting (not fasting), hares & deer, rosaries, prophetic dreams, bone-throwing as divination, Hildegard von Bingen, bestiaries (the unicorn, the griffon), mudlarking…

oh black soil, you blot and spoil

my precious pearl without a spot.

— from Pearl, the Gawain-Poet, trans. by Simon Armitage

Mabon is upon us. The mists are arriving. They are ridden by the damp white horses of the forest; heralds of the haunted month, month of the dead. (Tilda feeds them apples while I sleep.) Summer has rotted suddenly away in our hands. Earthworms and beetles crawl through our fingers — lovely, lonely creatures, September’s familiars. Our white dresses and stockings cannot disguise the mud underfoot. We tread Biblical names: St John’s wort, devil’s bit. I take out my furs from the recesses of the house.

There is something medieval about the autumn. It is a symptom of the desire to retreat, I feel — to the soil, to the hearth. The new academic year is upon us; we are remade as scholars and anchorites, finding hermetic refuge in libraries and chapels. On visiting the London Library this week I hunt immediately for the Psalms (under R: Religion) and Illuminated Manuscripts.

This is a medieval impulse, and feminine too.

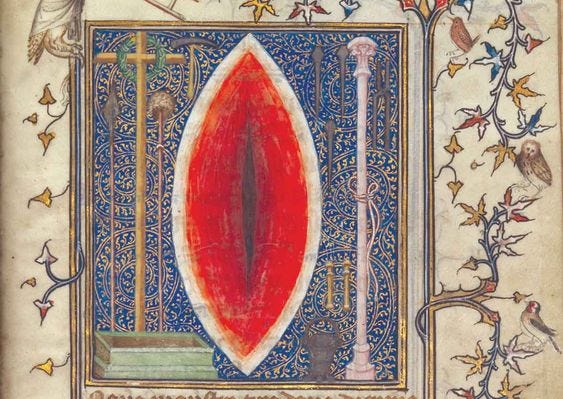

Three autumns ago in Cambridge I spent my Michaelmas term steeped in medieval literature. I devoted myself to Julian of Norwich, infected by her devotion, her revelations. Her theology hails the female body as sacred, inclined toward Spirit. To her, the Passion of Christ resembles the suffering of a mother in childbirth, the blood of the stigmata the nourishing milk of Mary.

But oure very moder Jhesu [...] susteyneth us with in hym in loue and traveyle, in to the full tyme pa t he wolde suffer the sharpyst thornes and grevous paynes that evyr were or evyr shalle be, and dyed at the last’ (60.14).

And I adored Pearl, a dream-vision born of grief and faith and their negotiation in aesthetic (im)perfection. Every formal aspect of the poem is contrived to resemble the wholeness and purity of the pearl, which in turn represents death’s redemption of a maiden into a bride of Christ.

I am not proposing to adopt the asceticism of the anchoress, or the suffering of the girl-saint (citing, again, the list of canonized women: Catherine of Siena, Saint Agatha, Jeanne d’Arc, Catherine of Alexandria, Saint Lucy…). I resist desiring the imitatio Christi, holy pain sought through fasting, flagellation, the punishment of female flesh. But there is something alluring about the ecstasy of female medieval mysticism, and the weirdness.

Belief in that period was plastic, like clay — boundaries worn away between the mystical, superstitious, scriptural. I think of Margary Kempe’s flagrant disregard of masculine Church dogma in favour of her own personal, erotic intimacy with Christ — Christ as groom and husband and bedfellow. Recreated in the dream-visions in the film Benedetta, and the convent as a locus of creative liberty in Sarah Dunant’s Birth of Venus.

Folk rites possessed, to many, as much reality as the sacraments. See the ingredients of a love spell: deer hearts, honey, mandrake root, verbena, beetle wings, menstrual blood, henbane. The use of a hagstone and eagle-stone as protective and birthing charms. Scripture as incantation:

Joshua’s prayer that made the sun stand still and Christ’s word that made the sea stand still might be invoked to make thieves unable to move if they touched a devotee’s goods. Phrases from the Gospels such as ‘Jesus passed through the midst of them’ might be used to ensure safe passage through perils, or ‘not a bone of him shall be broken’ to heal a toothache.

— from The Stripping of the Altars: Traditional Religion in England 1400-1580, Eamon Duffy

The girls (Grace, Marta, Lily, Mathilda and the trinity of Isabellas) and I attend the Evesham medieval faire in July. We watch the battle re-enactment, listen to folk songs and arcane medieval instruments, befriend troupes clad in hand-spun, hand-dyed medieval dress. There is meat and mead and animal pelts. We buy orange-blossom mead, rabbit-furred knife sheaves and bone earrings (fox, badger)…

And pewter pilgrim badges, pinned to our breasts and ribbons at our necks: the ‘Winged Heart’ (mid fourteenth century, an emblem of the Virgin Mary in which the heart is carried by the Angel of the Annuciation), the ‘Assumption’ (mid fifteenth century, associated with Our Lady of Eton, the central figure of the crowned Virgin, supported by angels), and the ‘Swan’ (a Lancastrian symbol, used by the heirs Henry of Monmouth and Edward, son of Henry VI).

(I wrote about the aesthetics of armour and amulets in January. Since then Alex made me a chainmail necklace for my birthday, onto which I tied a pearl cross.)

Under the dirt, from the weeping Virgin, in the street-side shrine — a cry —

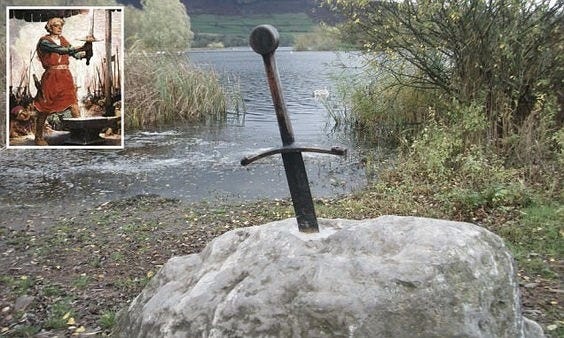

Let us throw our phones in the lake! Let us wield our swords and talismans in their stead, guard against the falling darkness! Let us greet Morgana, Guinevere, the lady of Avalon — let us practice our devotions madly and deeply!

with love,

Anna <3

lunulae.co.uk

insta: @anna.c.dewaal and @lunulaezine

oh i think you're the coolest ever

YOUR WRITING IS SO DELICIOUS