#hell is a teenage girl #waifspo #girlhood #girlblogging #coquette #dollette #femcel #female hysteria #divine feminine #just girly things #whisper girl #manic pixie dream girl #lana del rey #this is what makes us girls #girl interrupted syndrome

— for reference — the bread and butter of the Tumblr Sad-Girl, c.2024… ౨ৎ˚˖ ࣪⋆𐙚₊˚⊹♡

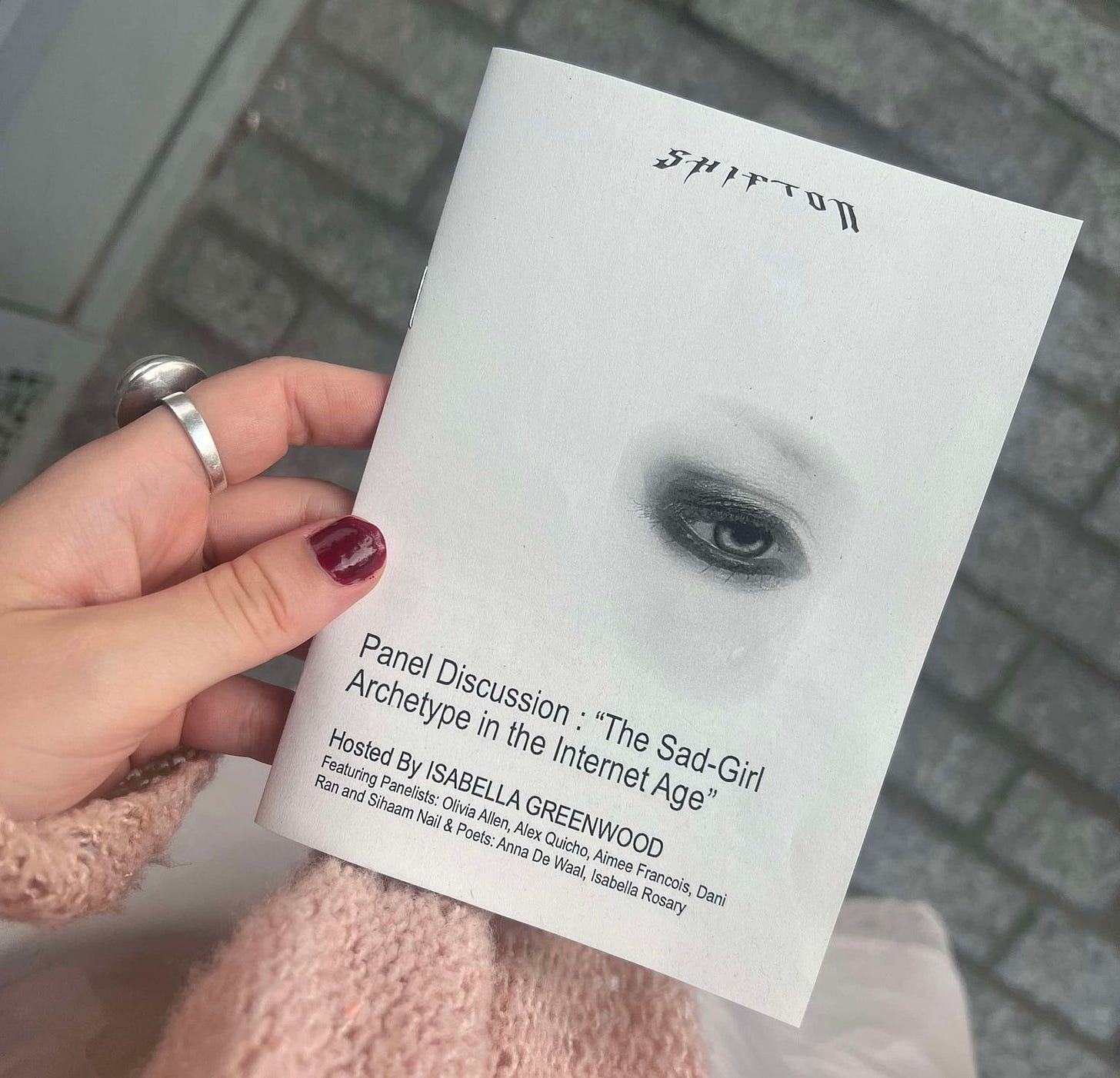

I was very honoured to read some of my work (printed at the end) at the panel discussion ‘The Sad-Girl Archetype In the Internet Age’, hosted at Shipton Gallery by Isabella Greenwood, August 30th.

Panelists: Sihaam Naik, Olivia Allen, Aimee Francois & Alex Quicho. Featured poets: Isabella Rosary, Aro Ha & ˚ʚ Anna de Waal ɞ˚.

Who is the Sad-Girl? She ‘bed-rots’ in her white nightdress, listens to Lana Del Rey, reads Sylvia Plath, identifies with the twin-headed lamb, Odette and Odile. Her medication bottle is tied with a pink ribbon. She is a porcelain doll, a Victorian waif wasting away, pale and thin and sickly — her sadness is lovely, her suffering romantic. Her wounds are fertile and unmistakably feminine. She is sister to the ‘Literary Sad Woman’, ‘our favorite tragic victim, our repository of rarefied, elegiac sadness’. Her skin is as white as snow, lips red as blood… etc.

I’m a fountain of blood in the shape of a girl

— from ‘Bachelorette’ by Björk

She is real and she is fabricated, witnessed and affirmed by her digital audience. And I have, unconsciously or otherwise, whittled myself into her — I am describing myself, or, rather, my public identity. I am not sure how to separate the two. I have been creating myself digitally since I was thirteen with my first Tumblr blog, posting images of Monotropa uniflora (ghost pipe) and deserted churches and the Spring 2006 Christian Lacroix couture runway. It was these early days of Tumblr that many iterations of the Sad-Girl were birthed.

Growing up as a girl on Tumblr groomed you to be prey. Before ‘coquette’ there was the ‘nymphet’, derived from Nabokov’s Lolita — under this tag you would find girls posting gifs of 1997 Dolores under the sprinkler, daydreaming about their ‘TC’ (teacher crush), posting pictures of themselves in white-frilled bloomers. Victimhood was not merely romanticised; it was actively sought out. The ‘nymphet’ was twinned with the cult of ‘pro-ana’ — the worship of anorexia, in which sickness was the ideal.

These sensibilities have pursued us into adulthood. We know this. The Sad-Girl phenomenon has been observed and recorded a hundred times over in cyber-feminist texts — see my ‘girlhood’ reading list. As Rayner Fisher-Quann has articulated, ‘young women are conditioned to believe that their identities are defined almost entirely by their neuroses’ — curated lists of aesthetic properties, as above, implicitly serve to ‘chicly signal one’s mental illnesses to the public’. With the advent of the internet, there is no longer such a thing as a neutral expression of self. The Sad-Girl is an avatar — a necessary degree of falseness is built into her.

even when i am ostensibly at my lowest, i am still filtering my experiences through the eyes of a consumer; the desire to editorialize our own experiences (to romanticize the unseen, to live for our biographies) has become an autonomic facet of womanhood as unavoidable as breathing.

— from Rayner Fisher-Quann, ‘standing on the shoulders of complex female characters’ ୨ৎ

Does the performance of suffering — and its transmutation into art — negate its ‘actual’ experience concealed somewhere beneath? Is not everything a pretension? As Alex Quicho argued on the panel, ‘so much of being alive requires that kind of falseness as a protective measure’. To inhabit the Sad-Girl archetype is both poison and antidote. She is, to Alex, the ‘shadow or Lilith for our ultra-productive, performative, smooth, shiny, capitalist girl selves.’

All this sits upon my heart, heavy and insistent. I am writing a novel about the dissociative retreat into the Dream-realm as a response to the traumas of girlhood — including and especially that absolute, predatory loneliness that sits inside the child and eats her from the inside out. The unconscious wishes of the girl (she has no name) turn uncanny and nightmarish. She encounters her dolls life-sized and speaking, is forgotten by her parents.

This project of my novel, and of this newsletter and lunulae — every thing I make, really — is my attempt to negotiate the relations of aesthetics and illness and girlhood. To study the cults of the female martyr, of Catherine of Sienna and Jeanne d’Arc and the Lisbon girls, the scriptures of Black Swan, Girl Interrupted, Anne Sexton’s verse… To try, and likely fail, to avoid kneeling at that altar, hands clasped, blood-stained, praying.

I have been conditioned to believe that suffering beautifully is a feminine activity. This is a dangerous philosophy. Pain is simply not beautiful — this should be the most plainly evident thing in the world. I wrote about this a little in my essay ‘lamb-child’, and how the reality of my illness was disagreeably ugly. Leslie Jamison writes:

How do we represent female pain without producing a culture in which this pain has been fetishized to the point of fantasy or imperative? Fetishize: to be excessively or irrationally devoted to. Here is the danger of wounded womanhood: that its invocation will corroborate a pain cult that keeps legitimating, almost legislating, more of itself.

These are the two poems I read at the panel. I wrote them both aged sixteen, and published them to my Tumblr. At this age, dissociated and wildly lonely, I did literally believe I was a spectre — lost on the other side of the looking-glass, a world parallel to reality. My writing was not simply a public staging of an artificial aesthetic self, but a symptom of my deep and desperate desire to be understood. I had no other reference for my experiences other than my own strange scraps of ghost-writings.

untitled #1

I knew a girl made of mist, once. on the first

day of school she held my hand and I gave her

my favourite velvet ribbon. we lay on the fields

and looked at the clouds, and she started to

cry — almost howled —

softly, if one can howl softly.

she left me, my girl.

she said she was going home.

I see her in my dreams, sometimes. she

doesn’t turn. when I wake

my cheeks are damp

with dew.

untitled, #2

there’s a doll in my bed —

ghost-pale skin, dusty hair, wide

glass eyes. she’s wearing my

nightdress. its thin whiteness

makes her look sad and small,

a little Snow White imposter

in her little open coffin.

I love my doll. I dress her up,

kiss her hair, tell her to play nicely –

keep quiet, don’t cry, you’ll spoil

your silk. when the porcelain splinters

I mend her with cobweb lace

and wood-sap glue.

As psychotherapist Aimee Francois discussed on the panel, there is this yearning tension between the need to render one’s sadness into art that is delicate, and the much less palatable violence and terror that also wants to speak. I wonder how to reconcile the two.

Anna <33

lunulae.co.uk

@anna.c.dewaal & @lunulaezine

so beautiful, put my constant thoughts and musings into words

achingly beautiful dear Anna🤍